“At the end of the summer of 2016, when it became clear, that I would spend more time in Poland than I had originally intended, I visited Ania in her new apartment. It was my first time in Wrocław. I had already heard a short history of the city as told by our friend Marcin. After the war all the Germans had to leave. New inhabitants moved in. They came mainly from the East, from the former Ukrainian part of Poland. Many years after the war the city still had not been rebuilt. It was a city of potholes and empty lots, of gaps and abandonments, with planning on paper, but not on the ground. I thought that I could see this, when I looked at the inner courtyard from the kitchen window. It was a massive courtyard, bigger than a football pitch, no trees, hardly some grass. Storage places stood in long lines, all of them with a different coloured door, that would open by lifting the handle and sliding it back under the ceiling. Cars could park on the grid; children played football on an artificial court. Gypsies sat in the shade of their little garage, had a drink or a talk. The men would occasionally walk a couple of meters away and piss against a wall. It was relatively silent, no shouting, no arguing, no fights. I was looking at life in a central European town. The town itself felt very open, as if the sea was near. Time seemed to pass in slow motion, yes, sometimes I thought that it came to a halt. I didn’t know anything. I didn’t know anything at all. It was the year 2016, but it easily could have been 1972 as well. And yet, to Ania it seemed all very natural. She was happy that she had found her blender, put the lid on it and filled the kitchen with the grinding noise of the machine. She prepared almond milk.”

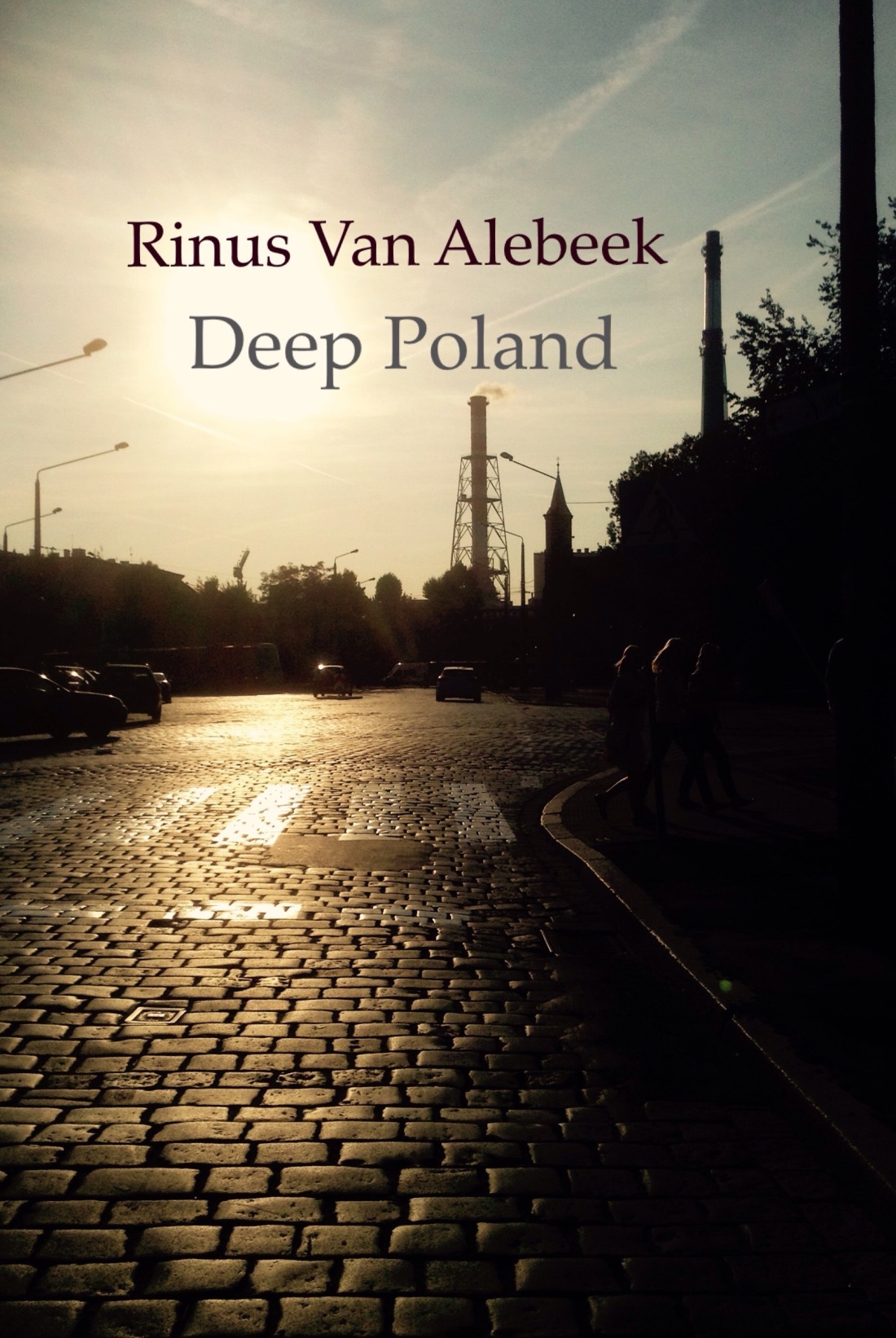

The ePub Deep Poland is available at the staaltape shop